Orbital Mirage

Following the Salty Glitches series, Orbital Mirage continues an ongoing investigation into the representation of satellite imagery in geo-visualization software such as Google Mapping Services. The work combines two media: a participatory map enables one to locate, document and monitor a series of glitches, while a projection of stills shows them on reversal film.

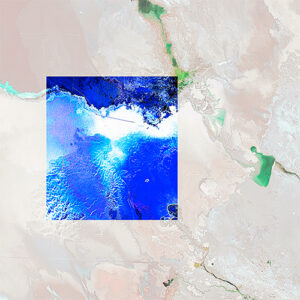

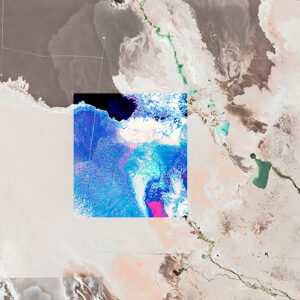

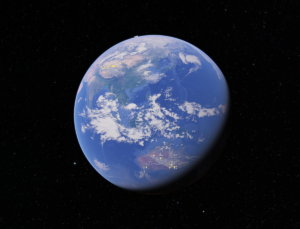

Evoking the natural phenomenon of a mirage, appearing under specific circumstances and dissolving as the viewers body approaches, the zooming in and out of the glitches makes their appearance and intensity also vary in response to the simulated position relative to the 3D earth object.

While the satellite imagery complements an ever-growing archive of images searchable on Google Earth, the glitches‘ transience and evanescence slip away from the digital corporate search and database systems. Orbital Mirage questions the logic and technology of mapping and aims to represent a counter-archive offering the possibility to deepen the exploration of glitches as a media-aesthetic otherness.

Excerpt of my reflection on Orbital Mirage focussing on the zoom function

Zooming in Google Earth creates new links between the virtual subject and the 3D object by unexpectedly unfolding the space into multiple images. This process is usually taken for granted, so that unnoticed, an image archive is available that is ordered by coordinates rather than a timeline or titles. Zooming therefore contributes decisively to the sense of continuity. Then it must also be elementary when continuity falters. This becomes particularly evident when we take a closer look at the glitches that become visible when zooming over an imaginary line at a certain distance from the 3D earth object. On the one hand, the medium emerges in these interruptions of continuity. But to focus purely on the disruption in the medium and the technology would be to fail to recognise that the glitches also give rise to something new, which contradicts the actual logic of the platform. They allow novel thinking in several directions at once.

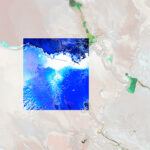

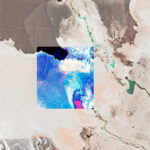

Oriented towards the backstages of representation, they point out to the Clip-/MIP mapping as a programmed invisible texture that remarks which imagery is displayed in Goolge Earth. Further, it is possible to think about the production processes and the (largely automated) work „behind“ the images. Satellites do not use one lens for their photographs, but are equipped with several lenses that can measure light of different wavelengths. The Google Earth image is composed of automatically stitched images from three lenses that together map the additive RGB colour space, and an additional infrared lens that measures the elevations of the topography. Glitches open up „un/visible spaces of interaction“ (Linseisen, 2022) by evoking a media-reflexive engagement with the software code and the (material) means of production.

On the other hand, they unfold when they are removed from the mere functionality of the medium and recognised as a media-aesthetic otherness and are introduced as realities of the (digital) world: Orbital Mirage’s glitches, for example, are not rigid objects in the otherwise static vertical photographs from Earth’s orbit, but are performative refusals of Google Earth’s world in the first place as they become in-the-zoom. In reference to the natural phenomenon of a mirage, which appears due to temperature differences on the earth’s surface and dissolves when approached, the glitches also suddenly appear on the screen from a certain viewing height and lose their intensity depending on the approaching virtual position of the subject. They hijack the discourse of the binary-coded world and register as the possibility for something that lies in between, resisting the mere order of a pure representation and creating new areas of potential for the possibility of their becoming.

The glitches boycott the visual habit of a seamless Google Earth. It is no longer the truthfulness of the world that is the object of observation, but the truthfulness of its representation and its representational surplus: a „Too Much World“ (Steyerl, 2013).

At the same time, the glitches are subject to the programme’s unpredictable processes of change. They are located exclusively in the now of Google Earth, but not in the database of historical satellite images. With each update of the image material, they are listed anew. Despite their rebellion against the platform, they are bound to its digitally conditioned reality. And so the glitches tell an unrecorded story of their transience and their mediation between satellite images and their representation.

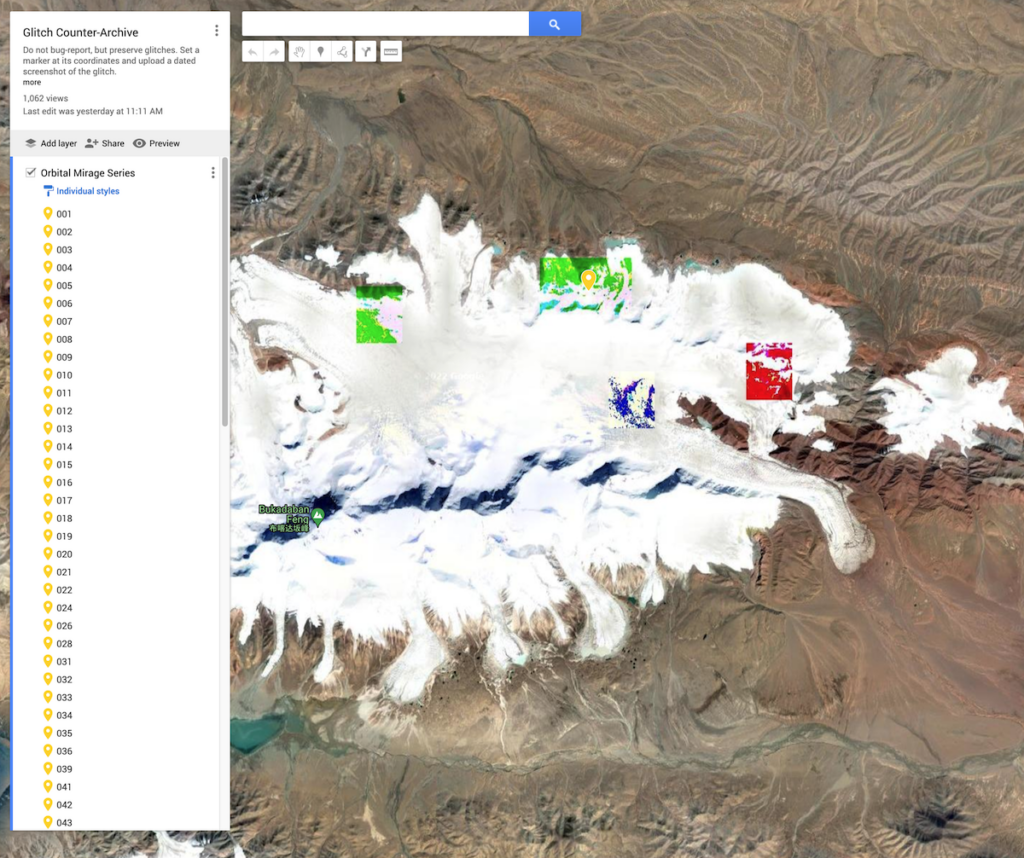

The Orbital Mirage project is dedicated to this narrative. It calls for solidarity with the glitches and combines two forms of representation into a counter-archive: In a public Google map, the participatory Glitch counter-archive, they are located and uploaded as screenshots. This is an attempt to collectively document the processual changes so that they can potentially be further investigated. By storing them, the narratives of the glitches become reality. They become political.

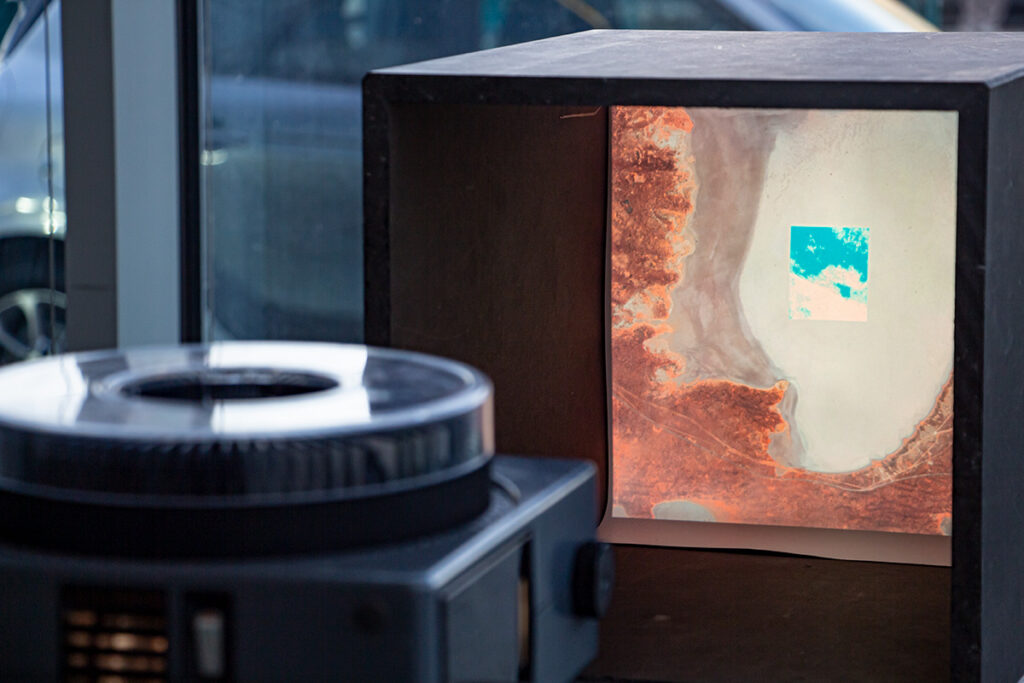

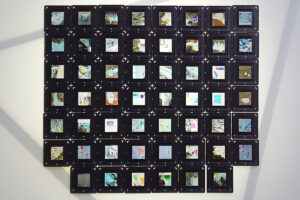

With the exposure on slide film, the counter-archive takes on a physical dimension. The enlargement of the small slides by the slide projector can be described as the analogue counterpart to the zoom enlargement on the computer or on the smartphone. At the same time, the idea behind this is to transfer the ephemeral glitches to an analogue storage medium in which they can be archived in the truest sense of the word. Artistically captured and exhibited as media-aesthetic artefacts, this evokes a new space for reflection on un/visible realities. To elaborate, lets consider the transfer of the glitches to the slides not least as a reference to the beginnings of space photography and its dissemination through the Zeiss publication Lenses in Space. As such, it stands out in a quite remarkable way what unexpected narratives can be told through the glitches, independent of technological issues:

I came into contact with NASA slide film photographs of the 1960s and 1970s through the idea of the counter archive for the glitches on slide film. In the individual issues of the Zeiss publication there is a register of all the manned space flights of the USA completed at that time. Among them are listed the flights of Mercury 8, Gemini 6 and Apollo 7, whose crew members included Walter M. Schirra Jr – a distant relative. So the stories told by my grandmother Liselotte Rückwart, born Schirra, caught up with me, which fascinated me as an 8-year-old child and which I did not investigate further at the time.

Glitches can be described as unknown opportunities of the digital, because they expand the environments in which they occur by a multiple of its logic. As the example shows, they allow completely new spaces of interaction to emerge. While the internet has always offered the possibility of simple contact between two connected agents, it is the glitches inscribed in a platform that can draw connections right into people’s biographies and link the existing nodes of contact. In this respect, glitches can step out of the digital world on a personal level and expand the notion of its reality. Through their potential to make the invisible tangible, they become real.

Differently conceived, the Orbital Mirages are then simple disturbances in the digital image, aesthetically remarkable inscriptions in the media environment with reference to its production, or sites of longing and sources of a digitally expanded consciousness that questions the normalisations and power structures of virtual world representation and evokes new narratives. As with the sand in the desert, the glitches in the sea of pixels stand out as oases: they are colourful.

Linseisen, Elisa (2022): “Too Much World. Potenzialbereiche des Digitalen“. Keynote at ZeM-graduates‘ conference „un:reale Interaktionsräume“ in Potsdam (November, 2022).

Steyerl, Hito (2013): „Too Much World: Is the Internet Dead?“ availabe online: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/49/60004/too-much-world-is-the-internet-dead/.

Excerpt of my reflection on Orbital Mirage focussing on the zoom function.

Supervised translation from German via deepl.com

Zooming in Google Earth creates new links between the virtual subject and the 3D object by unexpectedly unfolding the space into multiple images. This process is usually taken for granted, so that unnoticed, an image archive is available that is ordered by coordinates rather than a timeline or titles. Zooming therefore contributes decisively to the sense of continuity. Then it must also be elementary when continuity falters. This becomes particularly evident when we take a closer look at the glitches that become visible when zooming over an imaginary line at a certain distance from the 3D earth object. On the one hand, the medium emerges in these interruptions of continuity. But to focus purely on the disruption in the medium and the technology would be to fail to recognise that the glitches also give rise to something new, which contradicts the actual logic of the platform. They allow novel thinking in several directions at once.

Oriented towards the backstages of representation, they point out to the Clip-/MIP mapping as a programmed invisible texture that remarks which imagery is displayed in Goolge Earth. Further, it is possible to think about the production processes and the (largely automated) work „behind“ the images. Satellites do not use one lens for their photographs, but are equipped with several lenses that can measure light of different wavelengths. The Google Earth image is composed of automatically stitched images from three lenses that together map the additive RGB colour space, and an additional infrared lens that measures the elevations of the topography. Glitches open up „un/visible spaces of interaction“ (Linseisen, 2022) by evoking a media-reflexive engagement with the software code and the (material) means of production.

On the other hand, they unfold when they are removed from the mere functionality of the medium and recognised as a media-aesthetic otherness and are introduced as realities of the (digital) world: Orbital Mirage’s glitches, for example, are not rigid objects in the otherwise static vertical photographs from Earth’s orbit, but are performative refusals of Google Earth’s world in the first place as they become in-the-zoom. In reference to the natural phenomenon of a mirage, which appears due to temperature differences on the earth’s surface and dissolves when approached, the glitches also suddenly appear on the screen from a certain viewing height and lose their intensity depending on the approaching virtual position of the subject. They hijack the discourse of the binary-coded world and register as the possibility for something that lies in between, resisting the mere order of a pure representation and creating new areas of potential for the possibility of their becoming.

The glitches boycott the visual habit of a seamless Google Earth. It is no longer the truthfulness of the world that is the object of observation, but the truthfulness of its representation and its representational surplus: a „Too Much World“ (Steyerl, 2013).

With the exposure on slide film, the counter-archive takes on a physical dimension. The enlargement of the small slides by the slide projector can be described as the analogue counterpart to the zoom enlargement on the computer or on the smartphone. At the same time, the idea behind this is to transfer the ephemeral glitches to an analogue storage medium in which they can be archived in the truest sense of the word. Artistically captured and exhibited as media-aesthetic artefacts, this evokes a new space for reflection on un/visible realities. To elaborate, lets consider the transfer of the glitches to the slides not least as a reference to the beginnings of space photography and its dissemination through the Zeiss publication Lenses in Space. As such, it stands out in a quite remarkable way what unexpected narratives can be told through the glitches, independent of technological issues:

I came into contact with NASA slide film photographs of the 1960s and 1970s through the idea of the counter archive for the glitches on slide film. In the individual issues of the Zeiss publication there is a register of all the manned space flights of the USA completed at that time. Among them are listed the flights of Mercury 8, Gemini 6 and Apollo 7, whose crew members included Walter M. Schirra Jr – a distant relative. So the stories told by my grandmother Liselotte Rückwart, born Schirra, caught up with me, which fascinated me as an 8-year-old child and which I did not investigate further at the time.

Differently conceived, the Orbital Mirages are then simple disturbances in the digital image, aesthetically remarkable inscriptions in the media environment with reference to its production, or sites of longing and sources of a digitally expanded consciousness that questions the normalisations and power structures of virtual world representation and evokes new narratives. As with the sand in the desert, the glitches in the sea of pixels stand out as oases: they are colourful.

Linseisen, Elisa (2022): “Too Much World. Potenzialbereiche des Digitalen“. Keynote at ZeM-graduates‘ conference „un:reale Interaktionsräume“ in Potsdam (November, 2022).

Steyerl, Hito (2013): „Too Much World: Is the Internet Dead?“ availabe online: https://www.e-flux.com/journal/49/60004/too-much-world-is-the-internet-dead/.

Exhibited at

Orbital Mirage (Solo exhibition). JvB e.V., Berlin. 28.07 – 13.08.2023

Hammer show. Zuostant, Berlin. 10.02. – 12.02.2023

un:reale Interaktionsräume. FH Potsdam. 04.11. – 09.11.2022